Converging in Parallel

[Format | Schedule | Participants | Location | About]

[Panel 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5]

Panel 4: Canadian Telecommunications -- Shifting out of Neutral?

10:45-12:00 -- Friday, November 10, 2006.

Moderator: Erik Ens (Economist, Telecom Policy Branch, Industry Canada).

Jump to panellist: Abramson, Gow, Longford, McTaggart, Powell.

1. Bram Abramson (BCL/LLB Candidate, Faculty of Law, McGill University). What conceptual divide exists between the academic (communication studies) and industry (service provider) views of the telecom policy arena? Does it matter?

There is no single industry view of the telecom policy arena -- at least, not any single, unified view. That's partly because different people play different roles within each service provider. The sales representative trying to get a handle on who her company is and is not forced to interconnect its in-building network with inside a recently-built condominium, for instance, probably has a pretty different take on the regulatory framework than does the regulatory manager trying to explain it to her. But, more importantly, different service providers and different market participants are positioned very differently vis-à-vis that framework. The provider thinking about its condo build has one set of demands. The rural wireless Internet start-up realising it's going to have to find some fibre to get where it wants to go, will often have quite another.

Understanding that there is no single industry view of the telecom policy arena is one of the things that academic work, at least in the communication studies arena, has thus far done quite poorly. It shows. There are many academic discipines out there with something to say about telecom policy. None of them have had much to say about Canadian telecommunications policy, as the Telecom Policy Research Panel pointed out. But I'm singling out communications studies for two reasons. First, its starting point is communications, not necessarily a particular approach to it: all the theory in the world considered understanding of what the theory is meant to help explain. And, second, by taking communications as its starting point, communications studies is porous: approaches that work better are welcome, multidisciplinarity is an option, and those with insights on communication policy and regulation from other fields -- economics, law, accounting, sociology, and so forth -- can be part of the conversation. If academic research is to help open up a constructive dialogue with telecom policy-making, in other words, communications is a great place to start doing it.

Unfortunately, we're a long way from there. Some very good, sweeping historical work on telecom policy in Canada has been undertaken. But there is very little sustained engagement in the communications research community with the twists and turns of ongoing telecom policy and regulatory files in Canada, and the Manichean view I alluded to above is partly responsible. Some views of communication studies, and perhaps even of critical engagements with policy within the communication studies endeavour, fall too easily into a series of binary oppositions, then a series of preferences which flows naturally out of those oppositions: critical, not administrative research; qualitative, not quantitative work; non-market versus market approaches; "neutral" versus biased carriage.

Yet what we need is exactly the opposite. Critical policy can be critical only if it looks deeply into the day-to-day administration of the policy process. Effect policy intervention demands excellent quantitative descriptions of what's taking place, and experiential insight into how those quantities have been sliced, diced, and reheated. Taking a multiprovider environment seriously means a serious engagement with what competition policy looks like and how markets act as regulatory tools, not ends in themselves. Some of the interesting early engagement that communications studies scholars made in the telecom field involved "myths": of technological inevitability, of technical determinism, and of corporate and institutional design choices dressed up as engineering minutiae. Perhaps, though, it is time to look at myths that lurk closer to home -- or else continue to maintain the kinds of views of the telecom policy arena that end up not mattering very much at all.

2. Gordon Gow (Assistant Professor, Faculty of Extension, University of Alberta). A multiplatform, multidevice media environment means new market entrants, ranging from large to small. Whose responsibility should emergency services be? What barriers do they create for new entrants?

A primary objective of regulatory reform in Canada's telecom sector has been to open markets for competition. In moving toward the realization of this objective, the unbundling of formerly vertically integrated networks has been a central strategy. Liberalization of customer premises equipment, followed by long distance services, and later the supply of various network services. An open network architecture model has continued to inform the policy framework for what Robin Mansell termed more than a decade ago "the new telecommunications" (Mansell, 1993). More recently, the economist Martin Fransman associated this trend with a movement in the global telecom sector toward "vertical specialization" within an emerging "infocommunications industry" of multiple platforms and multiple devices (Fransman, 2002). In the time since liberalization began in earnest in Canada, the normative framework for policy has shifted from one of vertically integrated networks to one that contributes to vertical specialization within each layer of interconnection space (Gow, 2005).

This shift has profound implications for public safety communications, which I mean to refer to a range of services continue to evolve with changes taking place in Canada's public (switched) telecommunications network. For the sake of brevity it is helpful to categorize public safety communications into three broad categories:

An example from the first category is 9-1-1 emergency services. An example of the second is public alerting/emergency broadcasting. In the former case, the telephone network provides a link for members of the public to contact emergency services for assistance. In addition to 9-1-1 the function, communications from the public may be integral to support of government situational awareness during public emergencies. In the latter category, the telephone and broadcasting networks are seen as vital links in providing the public with urgent, life saving information. In the third category, we find a range of other types of activities including priority access to dialing for emergency managers, critical infrastructure protection, and so forth.

A challenge to the supply of emergency services is their "public good" quality. As noted by Samarajiva, these kinds of services exhibit conditions of non-rivalry and nonexclusivity. According to conventional economic thinking on the matter, these two conditions, along with an associated free-riding problem, create a strong disincentive toward the private supply of public goods. In the face of this challenge, Samarajiva argues that public authorities have a responsibility to ensure the provision of emergency communications. In the case of public alerting he notes, for example, "disaster warning is part of the core business of government, by any criterion. In economic terms, it is a public good akin to national defense and has a tremendous impact on the economy. In political terms, it is a core element of the state, one that legitimates the existence of the state..." (Samarajiva, 2005).

Be that as it may, Samarajiva also acknowledges that in practice, cooperation between public agents and private suppliers is a necessity. While the imposition of regulations on private suppliers is always an option, in a context of market liberalization and rapid technological change this can prove to be complicated undertaking and one that might be less effective than other approaches. In world of growing information abundance, it may be less a question of forcing a direct supply of these services per se, and more a question of providing the right conditions for the flow of emergency communications services to take place from end-to-end across the network.

Let me offer two examples with which to illustrate my point. First is the case of "enhanced" 9-1-1 for mobile phones. Wireless E9-1-1 provides caller ID and location information to assist in emergency service dispatch. It provides a rough functional equivalent to E9-1-1 developed originally for landlines. Whereas the FCC in the United States chose to mandate Wireless E9-1-1 and then faced considerable difficulty in meeting its original targets, in Canada it was developed and gradually implemented through a negotiated rule-making process (Lawson, 1998) between the CRTC, mobile operators, and public safety answering points. The key vehicle for this was the CRTC's Interconnection Steering Committee, Emergency Services Working Group (CISCESWG), which over the years has proven to be an effective means of working out problems and developing solutions for an evolving 9-1-1 system in Canada. More recently, the CISC-ESWG has been focused on the problem of E9-1-1 routing for nonnative and nomadic VoIP providers. Despite this past success, a recent Part VII submission by Canada's PSAPs has indicated that more direct CRTC involvement might be required to ensure compliance among new entrants in the VoIP market (CRTC 2006).

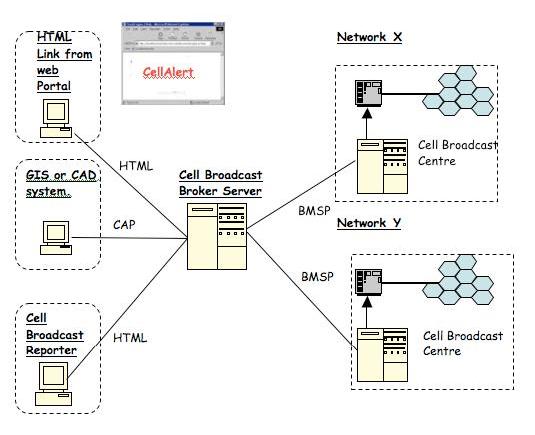

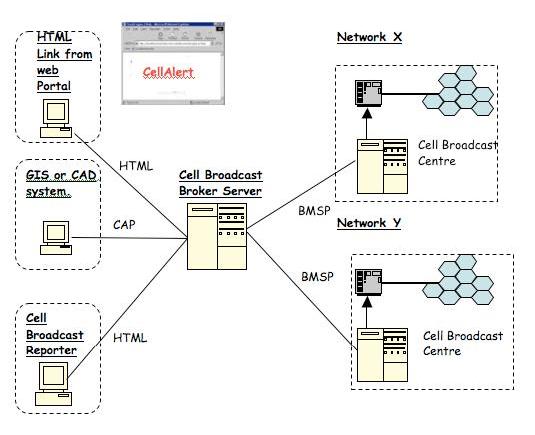

The second example involves the use of cellular broadcasting for public alerting, and this one raises what I think is a larger question for policy research in this particular area. Cellular broadcasting, or "CB" refers to a standard built in to GSM and CDMA networks that, among other things, enables public alerting over mobile phones without the inherent congestion and security problems that come with SMS-based solutions (Cellular Emergency Alert Systems Association, 2006). In Canada, a company based in Calgary called CellAlert has developed a secure platform for delivering public alerting over cellular networks using the CB technology (CellAlert Canada, 2005). Although it is not explicit in their marketing literature, it is probably the case that Cell-Alert views the offering of this "public good" as something that could be bundled with private commercial services via the CB technology, perhaps real-time traffic updates or news alerts, etc.

In effect we might consider CellAlert a new entrant with a vertically specialized innovation for an emergency communications market. This is an interesting case in part because it suggests that if conditions are right, then innovative R&D in emergency communications might receive a boost from private sector entrepreneurs seeking to bundle the technology with commercial offerings. One of the key factors in creating this condition, however, is access to essential network facilities. To test and refine its innovation, CellAlert needs access to mobile phone customers and, by necessity, to the "cell broadcast centre" component located within the mobile operators networks. At present, mobile operators in Canada have shown little interest in providing access to this network element for third parties such as CellAlert. In fact, following Mansell's political economy argument, there is a strong disincentive to providing access to the cell broadcast centre given that incumbent operators might consider such an innovation to be a threat to a potential revenue stream. So for the moment, it appears that companies like CellAlert must continue to try and negotiate access to this key network element if they are to ever to test and refine their innovation. Figure 1 shows a proposed architecture for a cell broadcast public alerting service.

This example illustrates the importance of gaining access to essential network facilities within a "vertically specialized" sector of converging media and device platforms. Essential facilities are those network components that have a special regulatory distinction. In Canada, a policy for essential facilities was established in CRTC Telecom Decision 97-8 in reference to CLEC entry. Within this framework they have three defining characteristics: it is monopoly controlled, it is a required input to provide services, and other firms cannot duplicate it economically or technically. If a network element falls within this definition then the CRTC can mandate terms and conditions of access to it. Under this definition, strange as it might seem, the 9-1-1 databases used for the provision of provincial E9-1-1 services do not appear to be considered essential facilities. Similarly, the cell broadcast centre needed by third parties to test, refine, and offer a public alerting service for mobile phones is not considered an essential facility. If the CRTC were to include this element as an essential facility, it could then mandate the terms and conditions for providing access to the CB centre, prompting further investment in and testing of CB-based solutions for public alerting.

Given this possibility, it seems that it might be time for a review of the essential facilities policy in Canada, with an eye to identifying those elements needed to encourage private investment in R&D for emergency communications services. The Australian regulatory body recognized a similar concern several years ago in considering the necessary conditions for the provision of unbundled communications services to emergency management organizations (Australian Communications Industry Forum, 2002). The Telecommunication Review Panel Final Report, issued in March 2005, included a recommendation that called for more explicit focus on "public safety" in Canada's telecom policy framework (Canada, 2006). This presents a timely opportunity for a comprehensive study of the policy and regulatory environment for emergency communications in Canada, and to identify the features a long term strategy that will not only safeguard the Canadian public but one that will actively promote innovation by encouraging R&D and the entry of specialized service providers.

References

Australian Communications Industry Forum. (2002, April). Industry Guideline: Communications Support for Emergency Response. Online: <http://www.acif.org.au>, accessed June 2002.

Canada. (2006, March 22). Telecommunications Policy Review Panel Final Report. Online: <http://www.telecomreview.ca/epic/Internet/intprp-gecrt.nsf/en/Home>, accessed June 2006.

Canada. Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. (2006, Sept. 27). 2006-08-17: 8663-B56-200610312 - British Columbia 9-1-1 Service Providers Association (BCSPA), Alberta E9-1-1 Advisory Association, City of Brandon Protective Services, Winnipeg Police Service, Ontario 9-1-1 Advisory Board (OAB), Association des Centres d'urgence du Québec (ACUQ), NB 911 Services/Services d'urgence N-B 911 Department of Public Safety/Sécurité publique, Nova Scotia, 911 Cost Recover Fee Committee and 911 Administrative Office Province of Prince Edward Island (the Applicants) - Routing of nomadic/non-native VoIP 9-1-1 calls. 2006. Online: <http://www.crtc.gc.ca/PartVII/eng/2006/8663/b56_200610312.htm>.

CellAlert Canada. (2005). Online: <http://www.cellalert.com>.

Cellular Emergency Alert Systems Association. (2006). Online: <http://www.ceasaint.org>.

Fransman, Martin. (2002). Telecoms in the Internet Age: From Boom to Bust to...?. London: Oxford University Press.

Gow, Gordon A. (2005). "Public safety telecommunications in Canada: regulatory intervention in the development of Wireless E9-1-1", Canadian Journal of Communication 30(1): 65-88.

Lawson, Philippa. (1998). "Procedural fairness and deregulation: a consumer advocate's view of the experience with telecommunications", Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC): Telecommunications. Online: <http://www.piac.ca/cbasp.htm>, accessed April 8, 2002.

Mansell, Robin. (1993). The New Telecommunications: A Political Economy of Network Evolution. London: SAGE.

Samarajiva, Rohan. (2005). "Mobilizing information and communications technologies for effective disaster warning: lessons from the 2004 tsunami", New Media and Society 7(6): 731-747.

3. Graham Longford (Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, Faculty of Information Studies, University of Toronto). What can policy research aimed at reducing domestic digital divides have to say to private service providers?

It is generally agreed among policy experts today that the ability of citizens and communities to access and make effective use of new ICTs (e.g. broadband networks) is vital to economic, social, political and cultural participation in the information society. Along with substantial public investment and community initiative over the last decade, private telecommunications service providers have established Canada as one of the most connected nations in the world. Having said that, a persistent and multifaceted digital divide continues to exist in Canada, afflicting the disabled, low-income households, rural residents, and Aboriginals. In addition, Canada's leadership position among the world's most connected nations is in jeopardy, as European and Asian countries have pulled ahead in the deployment of new products and services, including faster networks and wireless Internet service.

Bearing these two realities in mind, it is with concern that digital divide researchers note growing calls from private telecommunications service providers for increased reliance on market forces to shape Canada's advanced ICT infrastructure. In submissions to last year's Telecommunications Policy Review Panel, for example, private providers called for further deregulation and for the suspension of public investments in network infrastructure (e.g. BRAND program) in favour of market forces.

Market forces alone, however, will not ensure equitable and effective access to increasingly essential telecommunications infrastructure and services for all Canadians. Both experience and research demonstrate that, when left to the private sector, the evolution of Canada's telecommunications infrastructure fails to meet the needs of many Canadians. "Uneconomic" populations - rural residents, Aboriginals, the disabled - are often faced with poor service, high costs, or exclusion from service altogether. In an increasingly networked economy and society, such market-based forms of discrimination and exclusion are unacceptable. Furthermore, emulating the U.S.-style deregulation of the telecom sector, where broadband services are now among the poorest and most expensive in the OECD, hardly seems a prudent strategy for ensuring universal access to advanced networks.

Private telecommunications service providers play a lead role in developing Canada's advanced ICT infrastructure, as evidenced by Telus's recently announced $600 million investment in broadband network upgrades. In the course of doing so, however, market actors should also work collaboratively with communities and governments to develop affordable services and ubiquitous access for all Canadians, and should resist the temptation to engage in such practices as "market creaming" that hurt communities.

Moreover, when governments and/or communities decide to invest in network infrastructure to meet local needs due to "market failure" or other factors, private service providers should not stand in the way (as we have recently witnessed, particularly in the U.S.). Such providers should support the preservation of space within Canada's policy and regulatory framework for public/community investment in network infrastructure to meet local needs and serve the public good. Such investments fill access gaps that private providers lack the incentive to address. By being more attuned and accountable to local needs and circumstances, community-based networking solutions are more than mere "duplicators" of market-based services. Furthermore, rather than obstacles to or sources of unfair competition in relation to market actors (as is often claimed), public investment and community-based innovation in network infrastructure can spur the diffusion and adoption of new technologies and services, ultimately stimulating market demand (e.g. the development of WiFi hotspots).

Ultimately, the policy differences between private telecom service providers and digital divide policy researchers reflects their differing conceptions of the significance of telecommunications services as, on the one hand, an industry and market to be developed within a competitive environment, and, on the other hand, an increasingly essential form of infrastructure in the 21st century to which all citizens should have affordable and equitable access. Digital divide policy research suggests an on-going need for Canada's telecom policy and regulatory framework to accommodate both, by recognizing the need for public investment and community-based initiatives designed to mitigate the digital divide.

4. Craig McTaggart (Senior Regulatory Counsel, TELUS Communications). Imagine an academic wanted to make a compelling case for network neutrality within the CRTC framework. What kind of research would they have to undertake? Would they be in a position to speak to the regulatory process in the first place?

In order to make a compelling case for a new network neutrality rule, a researcher would need to conduct at least the following three steps:

Step 1: Inquire as to whether a new rule is needed.

Step 2: Conduct an economic analysis of the impact of a new rule.

Step 3: Propose a new rule.

Regarding whether the researcher would be in a position to speak to the regulatory process, it is difficult to know because the CRTC does not cite the authorities on which it relies in its decisions. Unlike the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the CRTC does not have a research arm. The Commission solicits public comments in proceedings, but does not require expert evidence in support of those comments, which tends to diminish the role of academic research before the regulator. As the Telecom Policy Review Panel identified in its March 2006 final report, the relative paucity of Canadian academic work on the regulatory craft is probably related in large part to the lack of a market for such research. The researcher could intervene in an existing CRTC proceeding on net neutrality-related issues (if any arise), challenge the arguments and evidence put forward by other parties, and be prepared to defend his or her own arguments and evidence. The researcher would have to consider whether to align her or himself with one of the parties that regularly participates in CRTC proceedings, or rather remain independent.

5. Alison Powell (Doctoral Candidate, Department of Communication, Concordia University). What kind of policy research would help policymakers build frameworks for the Internet as a "public good"? What could telcos contribute to that research?

Policymakers need to understand not merely the Internet's utility, but also its material and technical qualities, in order to understand their role in configuring this still-developing network. This position paper examines how a material perspective might guide discussions of how to define it as a public good.

Raboy and Shtern (2005) define the the Internet as "basically a set of protocols (software instructions) for sending data over networks. In other words, it is a means of communication" (126). The authors then argue that communication is a public good, and the Internet, as a global means of communication, requires regulation that promotes the Internet as a global public good. As a network, the utility of the Internet is not diminished by its individual use. While others, such as Goldsmith and Wu (2006), disagree with the argument for global regulation, most researchers agree that Internet data networks are not a finite resource. However, these perspectives consider Internet protocols only; not the hardware or software that also make up the Internet.

Recent technical developments provide new ways of going beyond protocols. The delivery of Internet via radio waves at the 802.1x standard (Wi-Fi or Wi-Max) provides a new means of thinking of the Internet as a public good. Such wireless technologies use radio waves to distribute Internet signals, making sharing or broadcasting the Internet much easier. We have abundant examples of how to potentially capitalize on this technical capacity, from community Wi-Fi experiments to wide-scale municipal Internet provision schemes using wireless technologies. Many municipalities have decided to invest in broadband or Wi-Fi infrastructures in the absence of other inexpensive means of providing Internet access to their citizens. However, making the Internet technically easier to share does not mean that it can or will be shared. Making something publicly accessible does not make it a public good. For example, the Toronto Hydro Telecom Wireless project is based upon sharing existing infrastructure installed with public tax money, yet the model calls for users to pay charges for its use (Longford and Clement, 2006). This project provides a perfect example of the split between technical and economic possibility and policy. Policy-makers need to be able to see the relationships between the material potential presented by network technology and policy decisions that configure it.

Wi-Fi technologies also use license-exempt radio spectrum to transmit their signals. This spectrum, regulated by Industry Canada, is defined as a public good in national policy, but the vast majority of the radio spectrum, including bands recently opened, is auctioned to telecommunications companies, who obtain monopoly rights over specific bands. As most municipal and community WiFi projects rely on the tiny slice of license-exempt spectrum, opening more bands to license-exempt use would be a significant and important policy decision.

References

Goldsmith, Jack and Tim Wu (2006) Who Controls the Internet? Illusions of a Borderless World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Longford, Graham, and Andrew Clement (2006). How Long Will Toronto's Wireless Network be Free? Toronto Star, 7 September. Online: <http://www.thestar.com/NASApp/cs/ContentServer?pagename=thestar/Layout/Article_Type1&c=Article&cid=1157536268534&call_pageid=968256290204&col=96>, accessed 28 September 2006.

Raboy, Marc and Jeremy Shtern (2005) "The Internet as a global public good: towards a Canadian position on Internet governance for WSIS phase II". Pages 126-132 in Pauline Dugré, ed., Paver la voie de Tunis -- SMSI II. Ottawa: Canadian Commission for UNESCO.